Expert perspectives on the evolution of retina practice, procedures, technologies and instrumentation.

Ingrid Kreissig, MD

Why did cryotherapy undergo such a prolonged and winding path before being accepted in retinal surgery? The answer is relatively straightforward: at the time of its early introduction, there was no clinical necessity to replace diathermy as a method of inducing retinal adhesion. Thus, an alternative coagulation modality was not sought.

Historical Background

The first report on cryotherapy in ophthalmology dates back to 1933, when Battista Bietti, an Italian ophthalmologist, described its application[1]. However, cryotherapy was not integrated into retinal surgery. The reason for this initial neglect was that diathermy sufficiently fulfilled the clinical needs of inducing retinal adhesion in retinal detachment surgery. There was no perceived benefit in substituting one form of coagulation with another.

This situation changed dramatically in 1953. Ernst Custodis, a German ophthalmologist, introduced a novel approach to retinal detachment surgery that avoided the drainage of subretinal fluid. He proposed using an elastic segmental buckle applied only to the area of the retinal break, thereby eliminating the need for a full encircling cerclage[2]. However, in this technique, the retinal break was sealed using transscleral diathermy. Unfortunately, this form of coagulation necrotized the sclera and could lead to significant complications, particularly under the compressive force of the elastic buckle. Despite the advantages of this procedure—namely, avoiding intraoperative complications such as drainage, intraocular injections, and cerclage—it thus encountered serious limitations.

Clinical Setback and Continued Exploration

Initially, the surgical community embraced this less invasive technique. However, in 1960, the Boston Group reported severe postoperative complications, including endophthalmitis and even enucleation[3]. This led to the abandonment of the technique in both Europe and the United States.

Nevertheless, Harvey Lincoff in New York did not discard the concept. Although he, too, observed serious complications, he remained convinced of the underlying logic of the Custodis procedure. He sought to eliminate the source of complications by refining the surgical materials and technique. First, he replaced the polyviol implant with a tissue-inert sponge. Then, in 1964, he presented data at the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) showing that cryotherapy could also induce retinal adhesion—without causing scleral necrosis, a key limitation of diathermy[4].

Rediscovery of Cryotherapy

Before his presentation at the AAO, Lincoff was seated behind Bietti, who reportedly remarked that Lincoff was about to report on cryotherapy, something Bietti had published decades earlier. However, Lincoff's inspiration to use cryotherapy stemmed not from Bietti’s work, but from observing his dermatologist using a cryoprobe with liquid nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) to treat skin lesions. Intrigued, Lincoff borrowed the device, applied it to rabbit retinas, and observed localized inflammation leading to scarring and retinal adhesion. When Lincoff took the podium at the 1964 AAO meeting, he acknowledged Bietti’s earlier work and credited him as the first to describe cryotherapy for the retina. This gesture sparked a professional friendship between the two.

Experimental Validation

At that juncture, it was imperative to confirm whether cryotherapy could reliably produce a retinal adhesion of sufficient strength and stability over time. Around this period, I traveled to the United States to move away from the highly invasive surgical techniques then practiced at the University of Bonn—namely cerclage, drainage, diathermy, photocoagulation, and intraocular injections—which had yielded disappointing outcomes.

After visiting Charles Schepens in Boston and Ed Okun in St. Louis, I arrived in New York in 1969 to study Lincoff’s surgical technique. Initially surprised by my appearance—a young, blonde German woman—he assumed I was unfamiliar with retinal detachment surgery and simply interested in New York. However, I soon convinced him of my genuine intent to improve my surgical skills. I demonstrated my expertise in the Goldmann three-mirror contact lens technique, which I had acquired during a two-year fellowship in Switzerland and which had not yet been introduced in the U.S. I was then granted the opportunity to participate in a two-year experimental study involving 336 rabbit eyes. The adhesive strength of cryotherapy lesions was evaluated using mechanical traction testing. We confirmed that cryo-adhesions developed adequate strength by day 7, with further increase up to day 12[5, 6]. We also investigated different intensities of cryoapplication—light, medium, and heavy—and established their long-term stability during extended follow-up.

Integration into Clinical Practice

These findings laid the groundwork for clinical implementation. Upon my return to Germany and appointment as Chair of Ophthalmology at the University of Tübingen, I initiated the necessary long-term clinical studies:

1. We confirmed the adhesive strength of transconjunctival cryopexy lesions in sealing retinal breaks[7].

2. A 15-year prospective study of 107 consecutive retinal detachments, treated with minimal segmental buckling and cryotherapy—limited to the retinal break and without drainage—demonstrated that, after 6 months of attachment, the retina redetached at a rate of only 0.5% per year. Visual acuity in the treated eye remained comparable to that of the fellow eye, with only minimal age-related decline observed[8].

Towards the Least Traumatic Surgical Approach

For Lincoff and me, the next challenge was to determine whether an even less invasive approach could be developed—one that eliminated the need for any permanent buckle. Could a retinal break remain attached solely due to the adhesive strength of cryotherapy?

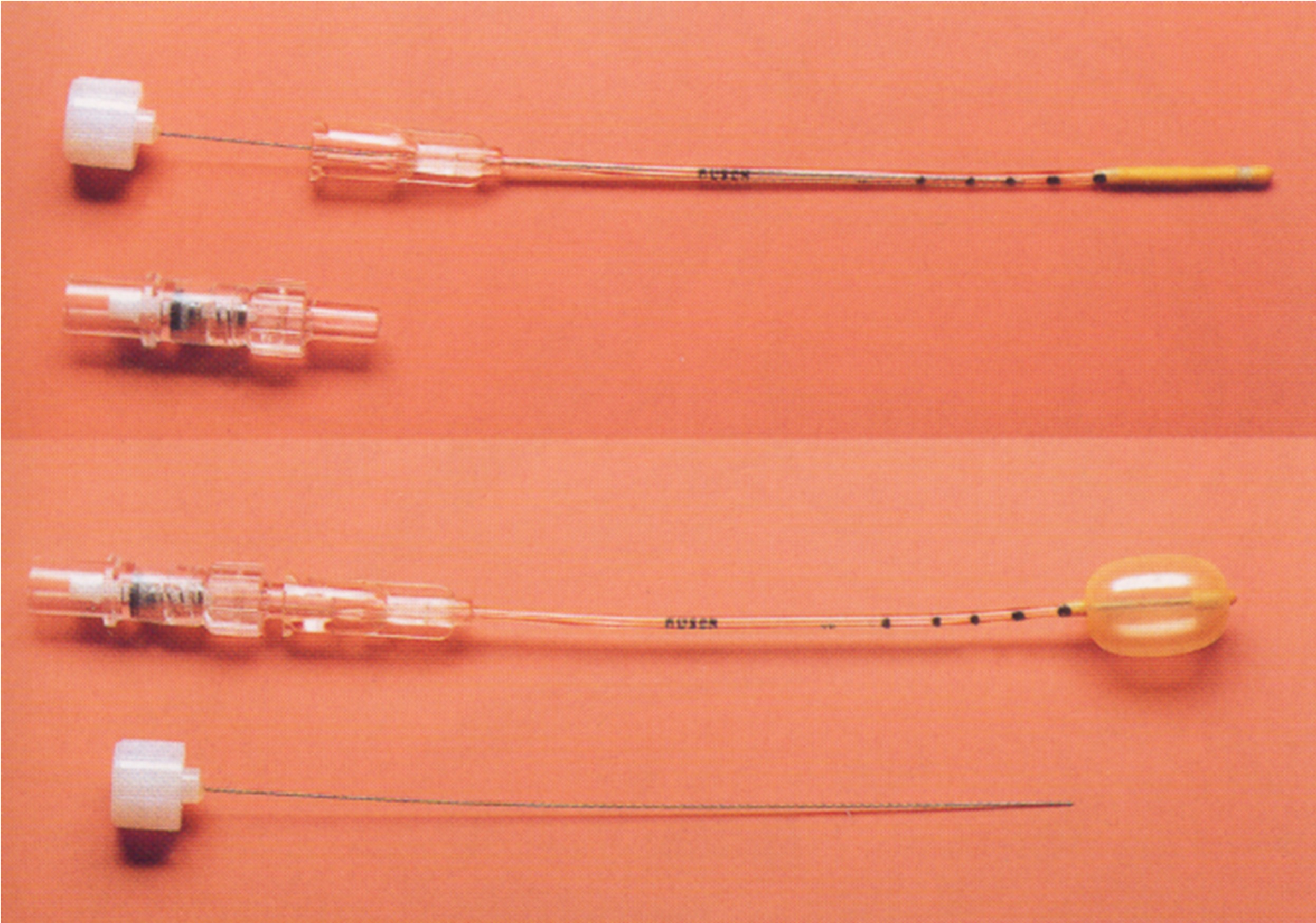

This vision led to the development of the Lincoff-Kreissig Balloon Procedure, which entailed a temporary balloon buckle, not sutured to the sclera, combined with transconjunctival cryotherapy limited to the retinal break and performed without drainage, under topical or peribulbar anesthesia[9]. The design and clinical approval of a reliable balloon catheter required three additional years and was realized in collaboration with the Ruesch Company near Tübingen.

Based on our prior animal studies, we knew that the balloon could be safely removed after 7 days, once cryoadhesion had matured. Balloon removal was simple: deflation via the adapter allowed the catheter to be expelled spontaneously from the conjunctiva. The retinal break remained reattached, confirming the adhesive strength of cryotherapy.

A consecutive series of 500 retinal detachment cases treated with the balloon procedure yielded promising outcomes:

Watch balloon surgery here.

The integration of cryotherapy into retinal surgery was catalyzed by the emergence of less invasive surgical techniques that could not tolerate the complications associated with diathermy. The use of cryotherapy, limited to the site of the break and performed without subretinal fluid drainage, enabled the evolution of retinal detachment repair toward truly minimal surgical approaches. This evolution culminated in the Lincoff-Kreissig Balloon Procedure, which offered a temporary, sutureless solution validated by both experimental and clinical data. Cryotherapy, initially overlooked and nearly forgotten, thus completed a remarkable odyssey—emerging as a cornerstone of modern retinal surgery.

References

1. Bietti G. Corioretiniti adesive da crioapplicazioni episclerali. Acta XIV. Conc. Ophth. Madrid (1933).

2. Custodis E. Bedeutet die Plombenaufnaehung auf die Sklera einen Fortschritt in der operativen Behandlung der Netzhautabloesung? Ber. Dtsch. Ophth. Ges. 58:102–105 (1953).

3. Schepens CL, Okamura I, Brockhurst R, Regan C. Scleral buckling procedures. V. Synthetic sutures and silicone implants. Arch. Ophthalmol. 64:868–881 (1960).

4. Lincoff H, McLean J, Nano H. Cryosurgical treatment of retinal detachment. Trans. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 68:412–432 (1964).

5. Lincoff H, Kreissig I. The mechanism of the cryosurgical adhesion. Part IV. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 71:874–889 (1971).

6. Kreissig I, Lincoff H. Cryosurgery of the retina In: Peyman GA, Meffert SA, Conway MD, Chou F (eds) Vitreoretinal surgical techniques. Martin Dunitz London 2001, 33-48.

7. Kreissig I, Sbaiti A. Kryopexie in der Ablatio-Prophylaxe (Cryopexy in the prophylaxis of retinal detachment). Klin. Mbl. Augenheilk. 159:588–596 (1971).

8. Kreissig I, Simader E, Fahle M, Lincoff H. Visual acuity after segmental buckling and non-drainage: A 15-year follow-up. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 5:240–246 (1995).

9. Lincoff H, Kreissig I, Hahn YS. A temporary balloon buckle for the repair of small retinal detachments. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 86:586 (1979).

10. Kreissig I, Failer J, Lincoff H, Ferrari F. Results of a temporary balloon buckle of 500 retinal detachments and a comparison with pneumatic retinopexy.

(Milestone essay published 2025)