Expert perspectives on the evolution of retina practice, procedures, technologies and instrumentation.

Edwin H. Ryan, MD, and Heinrich Heimann, MD

The most critical advance in retinal detachment (RD) treatment was performed by Jules Gonin, MD (Figure 1), who first recognized the importance of retinal breaks in RD pathogenesis. Prior to Gonin’s observations, a survey of ophthalmologists in the United States revealed a success rate in the range of 2% for RD repair.[1]

.jpg)

In 1918, Gonin reported to the Swiss Ophthalmological Society that the usual cause for a spontaneous RD was vitreous traction leading to a retinal tear, and in 1919 reported on his surgical successes in treating retinal tears.[2] This understanding was necessary for physiologic treatments to be devised for repairing RDs.

Gonin developed a procedure called ignipuncture (Figure 2), which involved marking retinal breaks, draining subretinal fluid, and applying diathermy. This approach showed increasing success rates and soon became accepted worldwide.

Over the next several decades, multiple approaches were utilized, including several methods for diathermy for retinopexy,[3] air tamponade with very good success rates reported by Rosengren,[4] and various approaches to scleral resection, which in effect was a form of buckling as it caused scleral indentation.[5]

A variety of approaches to scleral resection surgery, including both outfolding and infolding, and full-thickness vs lamellar resection, evolved over the next couple of decades. By the late 1950s, lamellar scleral resection was the dominant surgical approach at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, as well as with surgeons in the United States such as Harrell Pierce, MD, from Johns Hopkins, who by 1957 was using these techniques in 70% of cases.[6]

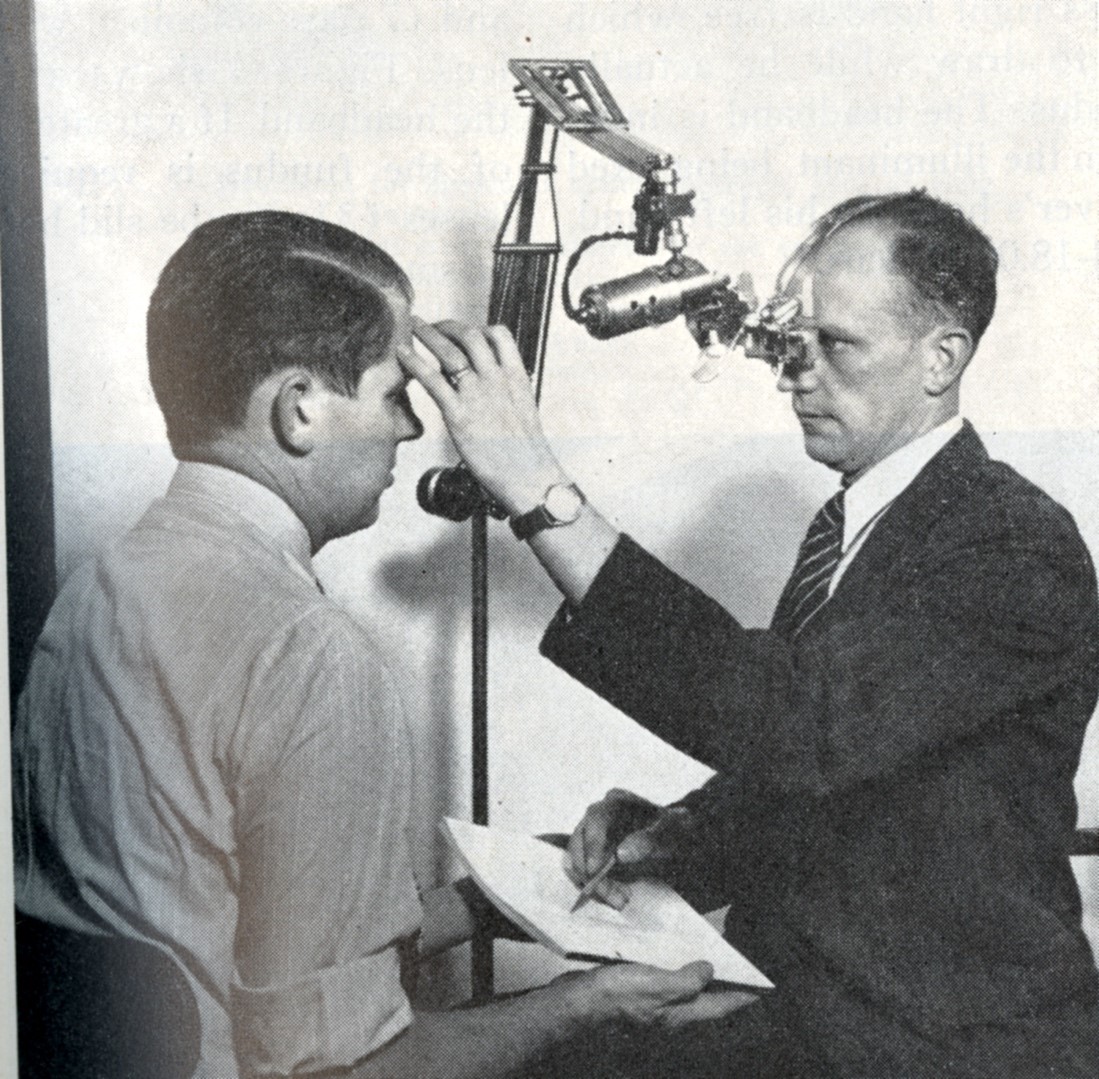

A giant step forward for correctly identifying the anatomy of RD and associated breaks was the binocular indirect ophthalmoscope, developed by Charles Schepens, MD. His first version, developed in 1947, was unwieldy, using an electric light source supported by a stand (Figure 3).[7] A head-mounted version was developed 4 years later,[8] and this basic design is still in use (Figure 4).

Schepens, originally from Belgium, moved to Boston after World War II. For years, he was reluctant to discuss his wartime experiences but later was honored as a war hero for his work in the Resistance.

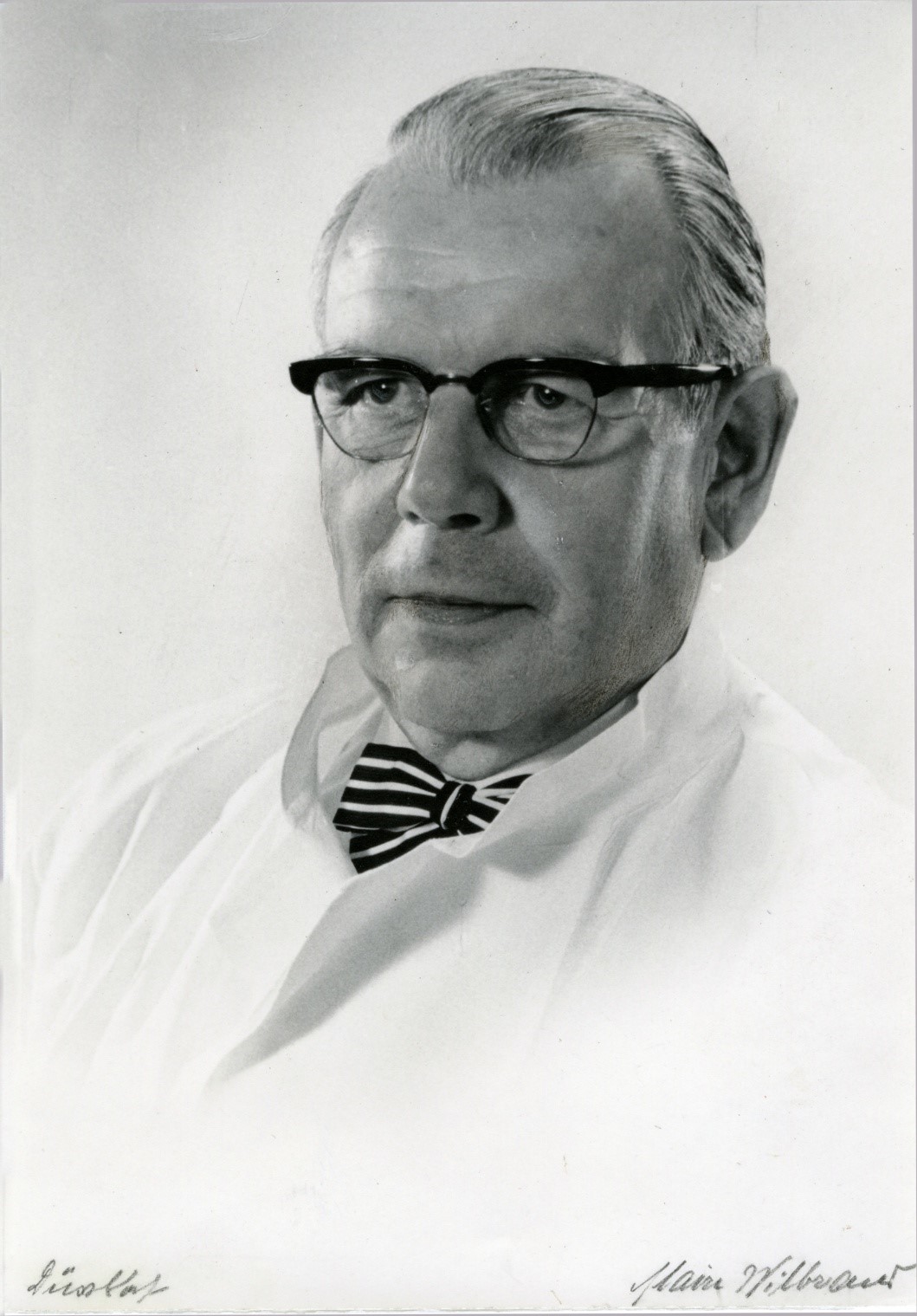

The first person to popularize the use of exogenous materials to close retinal breaks externally was Ernst Custodis, MD (Figure 5) in 1949.[9] He sutured to the sclera an exoplant made from polyviol, which is created by mixing polyvinyl alcohol with Congo red dye. This was usually modeled in a radial or segmental fashion and sutured in place without draining subretinal fluid. Previously, Jess[10] had used a cotton swab temporarily placed over the break after drainage of subretinal fluid, which was left in place for up to 14 days, then removed, but use of this method never became widespread.

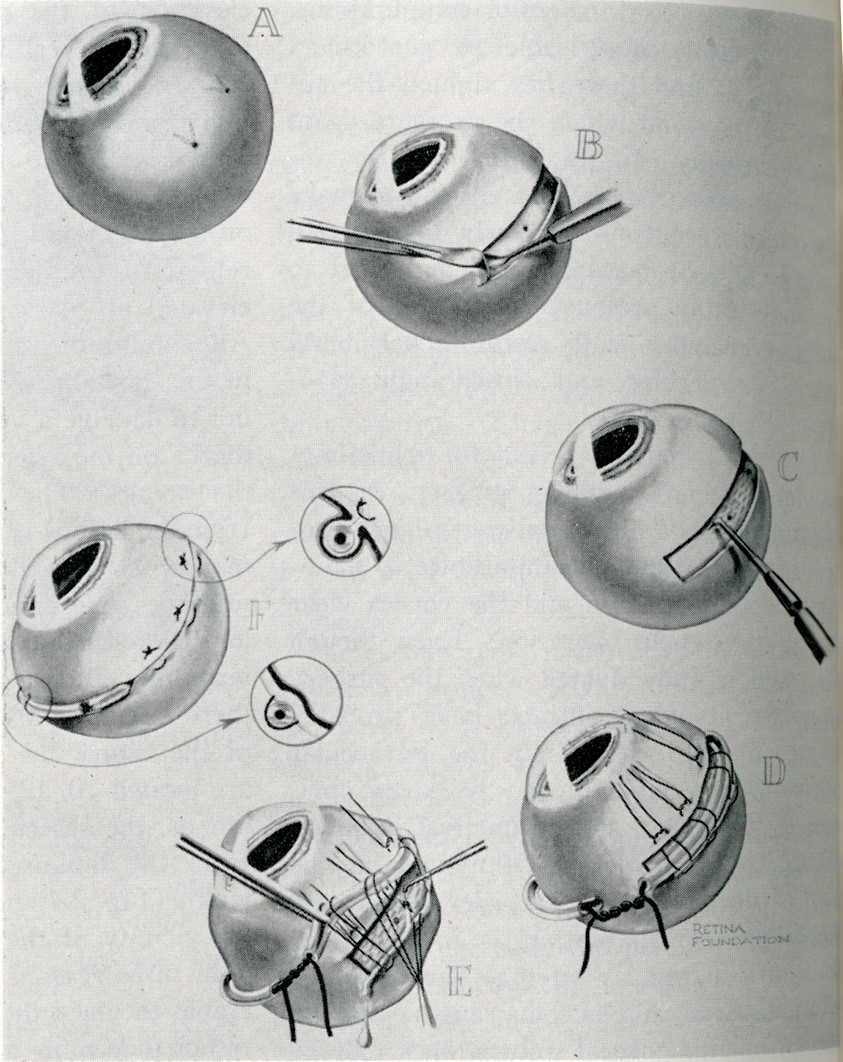

Scleral buckling using biocompatible materials was first performed by Schepens and coworkers in 1951.[11] They used partial-thickness lamellar scleral incisions, with an encircling polyethylene tube, and silicone implants placed in the dissection bed. Subretinal fluid was drained, and diathermy was used to create a retinal adhesion.

Over the next 15 years, a wide variety of segmental, then encircling procedures were developed using first lamellar dissection, then episcleral suturing of more pliable elements (Figure 6). This was an active era of innovation for scleral buckling techniques and materials.

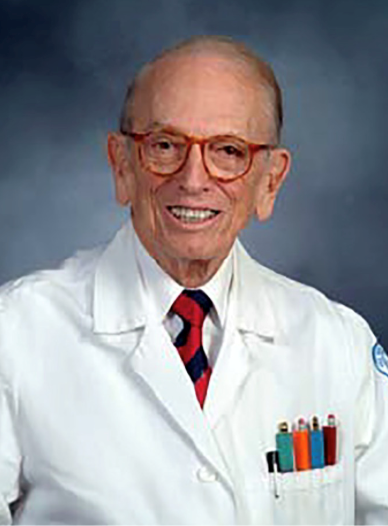

In the 1960s, Harvey Lincoff, MD (Figure 7) made 2 major contributions that advanced the field. First, he revisited cryotherapy using a device (Figure 8) employing liquid nitrogen for freezing effect, which had advantages over diathermy and thermal photocoagulation. It was not destructive to the sclera and did not require the breaks to be flat on the retinal pigment epithelium to be effective.[12]

Secondly, Lincoff popularized the reconsideration of non-drainage segmental and radial buckles, using chemically stable and inert silicone sponges.[13] Smaller, flexible solid silicone implants were developed and quickly became the standard for exoplants now used in encircling and segmental scleral buckling. With these materials available, scleral resection techniques are very seldom used.

MIRAgel implants, sold in the 1980s, were hydrophilic and intended to expand, increasing the buckling effect, and were initially reported to be safe and effective.[14] In many cases, however, these caused late-onset chronic inflammation, extraocular and intraocular migration, and orbital cellulitis. Use of these implants has been abandoned.

In the 1970s and 1980s, 2 developments threatened the dominance of scleral buckling. Vitrectomy was developed in the early 1970s, predominantly by Robert Machemer, MD, and coworkers,[15] and has evolved from an adjunct to scleral buckling to (in the view of some) a replacement for scleral buckling.

Pneumatic retinopexy[16] using long-acting gases was revived as a procedure and has had sufficiently high success rates to now be used to repair about 20% of primary detachments. It was beginning to appear that there may not be any role for scleral buckling in RD repair, but both authors of this account believe that data analysis rather than forcefulness of opinion should drive determinations as to the most effective surgical approaches for RD repair.

The authors organized and ran 2 large studies in the past 25 years that have conclusively shown an ongoing role for scleral buckling in phakic patients: the Scleral Buckling vs Primary Vitrectomy in Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment (SPR) Study in Europe overseen by Dr. Heimann,[17] and the Primary Retinal Detachment Outcomes (PRO) Study in the United States organized by Dr. Ryan.[18]

It is the authors’ conviction that scleral buckling will continue to be useful for RD repair for the indefinite future, and that it is imperative that the procedure be taught well.

Looking for more on this topic? Click here to watch the History of Retina’s expert panel discussion on scleral buckle featuring Drs. Gary Abrams, Buzz Kreiger, Mike Lambert, and Pat Wilkinson.

References

1. Vail DT. Poor outcomes in retinal detachment surgery. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1912.

2. Rumpf J. Jules Gonin. Inventor of the surgical treatment for retinal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976;21(3):276-284. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(76)90125-9

3. Larsson S. Electro-endothermy in detachment of the retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 1932;7(5):661-680. doi:10.1001/archopht.1932.00820120011001

4. Rosengren B. Results of treatment of detachment of the retina with diathermy and injection of air into the vitreous. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1938;16(4):573-579.

5. Pischel DK. Diathermy in retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1939;22:292-312.

6. Pierce EA. Resection techniques in retinal detachment surgery. In: Schepens, CL, ed. Importance of the Vitreous Body in Retina Surgery with Special Emphasis on Reoperation. C.V. Mosby; 1960:175-182.

7. Schepens CL. Early binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1947;51:298-306.

8. Schepens CL. Modern binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1951;55:389-397.

9. Custodis E. Bedeutet die Plombenaufnähung auf die Sklera einen Fortschritt in der operativen Behandlung der Netzhautablösung? Ber Dtsch Ophthalmol Ges. 1952;57:227-230.

10. Jess A. Kriegsverletzungen der Augen durch Gaswirkung, Verbrennung und… Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1937;99:1-2.

11. Schepens CL. Scleral buckling elements in retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953;36(3):408-420.

12. Lincoff HA, McLean JM, Nano H. Cryosurgical treatment of retinal detachment. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1964;68:412-433.

13. Lincoff H. Radial buckling in the repair of retinal detachment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1976;16(1):127-134. doi:10.1097/00004397-197601610-00012

14. Tolentino FI, Roldan M, Nassif J, Refojo MF. Hydrogel implant for scleral buckling: long-term observations. Retina. 1985;5(1):38-41. doi:10.1097/00006982-198500510-00008

15. Machemer R. Vitrectomy: a pars plana approach. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1971;75(4):813-820.

16. Hilton GF, Grizzard WS. Pneumatic retinopexy. A two-step outpatient operation without conjunctival incision. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(5):626-641. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33696-0

17. Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al; SPR Study Group. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2142-2154. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.09.013

18. Primary Retinal Detachment Outcomes Study Group. Report Number 2: Outcomes of primary retinal detachment repair. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):477-485.

Ryan EH, Ryan CM, Forbes NJ, et al. Primary Retinal Detachment Outcomes Study Report Number 2: Phakic Retinal Detachment Outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(8):1077-1085. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.007

(Milestone essay published 2025)